Bald Eagle

(Haliaeetus leucocephalus)

Almost everyone knows what an adult bald eagle looks like. We see its majestic image on our nation’s official seal, on one dollar bills and on postal trucks. That’s because on June 20, 1782, the bald eagle was adopted by the Continental Congress as the central figure for the Great Seal of the United States, representing “free spirit, high soaring and courage.” Its power and mystery were recognized well before then by early inhabitants of this continent, who drew its impressive likeness on silent canyon walls, carved its dignified figure into pottery and coveted its grand feathers for ceremonial purposes.

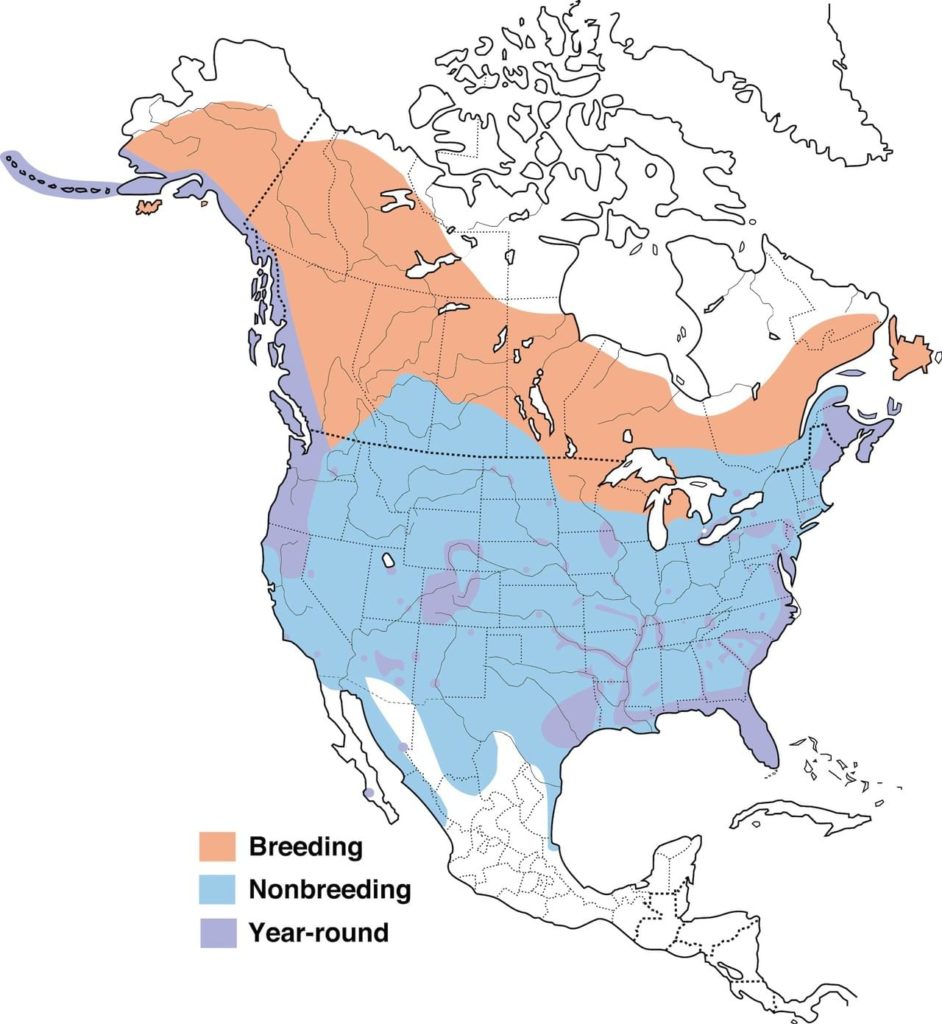

Although there are over 60 species of eagles worldwide, bald eagles are the only eagles found exclusively in North America, ranging from the Gulf of Mexico to near the Arctic.

They belong to a group of eagles known as “sea eagles, ” a fact directly reflected in the scientific name, Haliaeetus leucocephalus, the Greek wording for “sea eagle with white head.” Not exclusive to coastal areas, they usually occupy many areas associated with water such as lakes, rivers and reservoirs where they feed predominantly on fish, as well as ducks, coots, small mammals and carrion.

The bald eagle isn’t really bald as its common named suggests. The term “bald” comes from an old English word for white which was spelled “balde,” and refers to the pure white feathers covering its head. This gleaming white head and its white tail, in contrast with its very large, dark body make the bald eagle unmistakably recognized — at least as an adult. In their first four to five years of life, immature bald eagles have dark feathered heads and bodies, making them easily confused with golden eagles. They can be distinguished mainly by white mottling patterns on the undersides of their wing and tail feathers.

Utah hosts one of the largest state populations of wintering bald eagles with more than 1,200 counted statewide in recent years. This represents about 25 to 30 percent of the bald eagles wintering in the western half of the lower 48 states and indicates the significance of Utah’s winter habitat for bald eagles. Arriving in early November they often congregate in large numbers at feeding and roosting sites where they perch atop dead cottonwoods along rivers or coniferous trees at higher elevations. In the Red Cliffs Desert Reserve, they are most likely seen during winter (flying overhead). However, their hunting grounds are primarily at the local ponds and reservoirs.

Although abundant in Utah during the winter, bald eagles are rare as breeders. Only a few known nest sites exist within the state, with the closest being Kolob Reservoir (about an hour drive from St. George).